This piece was originally published in the Times Higher Education (05.08.22)

When the Conservative Party leadership hopefuls launched their campaigns at the start of July, the focus of one candidate, Kemi Badenoch, seemed different from that of the others. In addition to pledging tax cuts and economic growth, Badenoch used her platform to needle the UK higher education sector, taking potshots at universities’ brainwashing of students and their “pointless” degrees.

“Some universities spend more time indoctrinating social attitudes instead of teaching lifelong skills or how to solve problems,” she told The Sun newspaper on 11 July. The following day, writing for The Spectator, Badenoch expressed that anti-university sentiment in a way that was more coded but no less recognisable: “I’m not the sort of person who you can sideline, silence, or cancel,” she warned.

Badenoch has a reputation for HE baiting. When minister for equalities, in late 2020 she used Black History Month to pivot into an attack on critical race theory (CRT), accusing educators of presenting white privilege as fact to their students and describing CRT as “an ideology that sees my blackness as victimhood and their whiteness as oppression”.

The rhetoric was powerful, but it was also misleading. CRT is a set of cross-disciplinary tools and methods that emerged in the late 1980s for exploring racial injustices. It involves analysis of social structures, not individual identities.

The problem is that, as academics, we tend not to be very good at explaining our methodologies. Historically, we haven’t needed to because the separation of state and university was always enough to keep politicians’ noses out of our curricula. But those days have gone, and we must now find ways to articulate more clearly and more persuasively the value of our approaches.

In an age of culture wars, all kinds of petty non-stories can be blown up into a headline event if it is politically expedient to do so. Even a vaguely unpatriotic gesture by a small group of students can be seized upon by a government keen to divert voter gaze from its economic and social policy. Once outrage is manufactured, the truth matters little.

The temptation for universities is to look the other way until the news cycles roll on. But news cycles don’t roll on. For a public conditioned into distrusting universities, the idea that academics are secretly radicalising their students through CRT is depressingly plausible. So politicians and media commentators continue to fabricate or exaggerate tales of “wokeness” on campus: biased lecturers, student snowflakes, Mickey Mouse degrees and no-platforming.

A programme of marketisation has compromised universities, leaving them unsure how to rebut criticism like Badenoch’s. Discourses of the public good have been mostly displaced by a narrow, utilitarian focus on value for money. Right-wing governments realised that universities were a block to free-market thinking, so they sought to impose competition as disciplining strategy. Now the sector is losing confidence in its core social purposes.

Pushing back against increasingly populist forms of government isn’t easy. However, it is vital that the anti-university narrative isn’t allowed to take hold uncontested. Evidence of the limits of a quasi-market in higher education is ubiquitous: graduates repay loans for most of their working lives, but the cost to the state remains substantial; institutions spend millions on marketing, but price differentiation remains rare; and despite institutions being ranked in every way imaginable, traditional hierarchies of prestige are arguably stronger than ever.

Yet vice-chancellors remain reluctant to dissent. Many were quick to accept sizeable pay rises when the marketisation project began, seemingly unaware that they were being co-opted by the reformers. Meanwhile, the sector’s representative bodies stubbornly favour strategies of soft power and behind-the-scenes influence over more public confrontation. So market logic persists despite strong indications that it is neither sustainable nor equitable.

As academics, we are also sometimes complicit in our silence, swept along by tides of metrics and oblivious to the treacherous undercurrents. Those of us fortunate enough to hold permanent posts can turn blind eyes to creeping contractual and intellectual precarity elsewhere, preoccupied by – and sometimes enticed by – an embarrassment of individualistic metrics.

But a counter-narrative needs to emerge from somewhere. Someone needs to be pointing out that universities remain the lifeblood of many communities, particularly in straitened times, and that higher education is one of the few ways through which the status quo can be challenged. The culture wars and the snipes about academic methods are not inconsequential. They form part of an agenda to soften up the sector for further structural overhaul, and ultimately for cleansing society of critical or counter-hegemonic thinking.

Badenoch didn’t make it to the final two in the Conservative leadership contest. However, she progressed further than most commentators expected, and her anti-university sentiment played well with many in her party and beyond. Other politicians and strategists will have noticed the immense capital to be gained from a plain-speaking, anti-woke stance.

They may also have noticed that the UK higher education sector is a soft target because almost no one is fighting back.

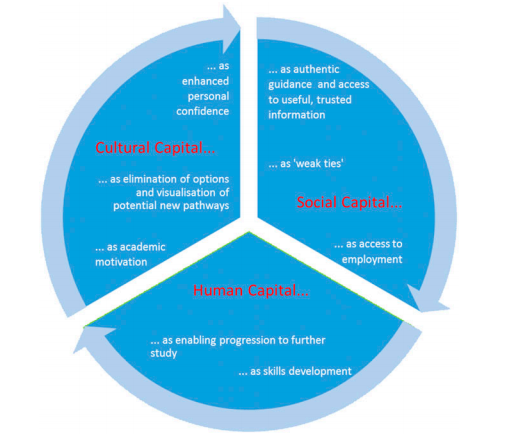

Within research and policy debates, increasingly it has been asked not whether employer engagement makes a difference to the prospects of young people, but why it does so and how it can be optimally delivered. Stanley and Mann (2014), for example, draw on insights from three inter-related concepts commonly used in academic and public policy literature to explain relative advantage and disadvantage experienced by individuals within the labour market: human, social and cultural capital.1024 Drawing particularly on work by sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and Mark Granovetter, Stanley and Mann offered ‘a theoretical framework that can comprehend accounts of how employer engagement is experienced and how it provides resources that aid progression in the labour market.’ In new research, this framework is tested for the first time.

Within research and policy debates, increasingly it has been asked not whether employer engagement makes a difference to the prospects of young people, but why it does so and how it can be optimally delivered. Stanley and Mann (2014), for example, draw on insights from three inter-related concepts commonly used in academic and public policy literature to explain relative advantage and disadvantage experienced by individuals within the labour market: human, social and cultural capital.1024 Drawing particularly on work by sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and Mark Granovetter, Stanley and Mann offered ‘a theoretical framework that can comprehend accounts of how employer engagement is experienced and how it provides resources that aid progression in the labour market.’ In new research, this framework is tested for the first time.