HEPI Policy Note 48, by Tom Fryer and Steven Jones, first published here on June 15th 2023.

Category Archives: UCAS

UCAS reforms to the personal statement: One step forward, more to go?

Originally published as HEPI Weekend Reading; written by Tom Fryer, Steve Westlake and Steven Jones

On 12 January, UCAS released Future of Undergraduate Admissions, a report that contained details of five upcoming reforms.

In the report, UCAS proposes to reform the free-text personal statement into a series of questions. This is welcome. As we noted in our recent HEPI Debate Paper on UCAS personal statements, an essay without a question is always going to breed uncertainty.

So the change does represent progress towards a fairer admissions system. However, the number of steps we take towards this fairer system will depend on how the questions are designed.

The UCAS report makes an initial proposal of six questions across the following topics:

- Motivation for Course – Why do you want to study these courses?

- Preparedness for Course – How has your learning so far helped you to be ready to succeed on these courses?

- Preparation through other experiences – What else have you done to help you prepare, and why are these experiences useful?

- Extenuating circumstances – Is there anything that the universities and colleges need to know about, to help them put your achievements and experiences so far into context?

- Preparedness for study – What have you done to prepare yourself for student life?

- Preferred Learning Styles – Which learning and assessment styles best suit you – how do your courses choices match that?

Our first point concerns inequality. To create admissions processes that address inequalities we should use questions that place explicit limits on the number of examples that can be used. If we leave questions open-ended, this risks creating a structure that allows some applicants to gain an advantage over their peers, a key problem with the original format. Also, where possible, questions should stress the acceptability of drawing upon activities, such as caring or part-time work, that may not be deemed ‘high-prestige’. This could minimise the impact of inequalities in access to these ‘high-prestige’ activities. The relatively small number of courses that require formal work experience could gain this information through an optional question.

Secondly, admissions processes should prioritise applicants’ interests and avoid imposing an unnecessary burden. The current proposals contain several questions that appear similar, which does appear to impose an unnecessary workload on applicants and their advisers. We recommend combining the second (course preparedness), third (preparedness through other experiences) and fifth (study preparedness) questions into one, in order to protect applicants’ interests.

Thirdly, other commentators have drawn attention to the association of ‘learning styles’ in question 6 with the widely debunked model that classifies people into four different learning modes: visual; aural; read/write; and kinesthetic. This does not seem to have been UCAS’s intention. Instead through informal conversations we understand the question intended to focus on applicants’ preferences for independent study versus contact time, or frequent short assessments versus substantive end-of-year approaches. Regardless, should applicants’ attitudes to learning and assessment influence admissions decisions? There could be a range of reasons why an applicant has chosen a certain provider, including geographical location for those with caring responsibilities, and many of these will trump concerns about learning styles. We recommend removing this question.

Fourthly, while the report gives evidence that many applicants see the personal statement as an opportunity to advocate for themselves, this alone does not justify the creation of a large number of questions (or indeed, nor does it justify the status quo). Unfortunately, a lack of transparency prevents applicants from understanding how their statement will be read (if it is read at all), and many will be unaware of the research on inequalities in this area. These caveats are important when considering how applicants’ views should feed into discussions about creating an admissions system that protects all applicants.

Our final point relates to validity. Admissions processes should use valid measures of applicants’ ability to complete their chosen courses. Although there is limited research in this area, we think there are opportunities to improve the proposed questions.

To take one example, the first question asks ‘Why do you want to study these courses?’. We contend that an abstract question is unlikely to be the most valid way to assess applicants’ motivations. This question is likely to prompt similarly abstract or cliched answers, including in the form ‘Ever since a child…’. As an alternative, in our HEPI paper, we proposed the following:

Please describe one topic that is related to your course. Please discuss what you have learnt about this topic, through exploring this outside of the classroom. This could include books, articles, blogs, seminars, lectures, documentaries, or any other format.

This question measures both whether an applicant demonstrates a basic level of motivation and whether they understand what is covered on the course. By asking for a concrete example of a topic they have explored, we believe this question is likely to be a more valid way to assess whether applicants meet a basic level of motivation and preparedness, and it is less likely to result in overly abstract or clichéd responses that reveal little about applicants.

UCAS’s proposed reforms to personal statements recognise that fair admissions require greater transparency, a more supportive structure, and the prevention of some applicants being placed at a disadvantage. Moving to a series of questions represents one step forward. However, to achieve these goals, the questions must be designed to address inequality and remove unnecessary burdens in a transparent and valid manner.

There is currently no published research on how personal statements are used in admissions decisions. That’s why we are launching a survey to gather some initial data, which you can access here.

We are particularly seeking input from people involved with the day-to-day work of undergraduate admissions. We would appreciate it if you could share this with any of your colleagues. We plan to use this data to feed into the public conversation about UCAS’s reforms.

It’s not easy to raise prior attainment, but universities could better contextualise applicants’ grades

Note: this piece was originally published here on LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog.

The government has challenged the Higher Education sector to double the proportion of pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds and to raise by 20 per cent the number of undergraduates from Black and Minority Ethnic backgrounds. However, last month’s report by the Social Market Foundation (SMF) casts doubt on the achievability of either goal.

Among the observations offered by the SMF is that the spread of disadvantaged students across UK universities is very patchy. While some institutions’ Widening Participation (WP) intake is pushing 30 per cent, proportions elsewhere barely top 2 per cent. No surprise there, perhaps. But what may come as more of a shock are differences in the rate of improvement. As the SMF graph below shows, progress since 2009 among Top 10 institutions (according to rankings in the Times Higher) is less than half that made by institutions ranked 11-20 and by those outside the Top 20. In other words, the rate at which the UK’s highest prestige universities are growing their WP intake is more sluggish than everywhere else.

Does that matter? Well, as the Social Mobility and Child Poverty commission has noted, the top professions tend to be dominated by alumni of the highest ranking universities. And according to the Sutton Trust, graduates from such universities enjoy the more substantial earnings premium. The risk is that the sector’s uneven distribution of WP students allows social hierarchies to be reproduced and causes social mobility to stall.

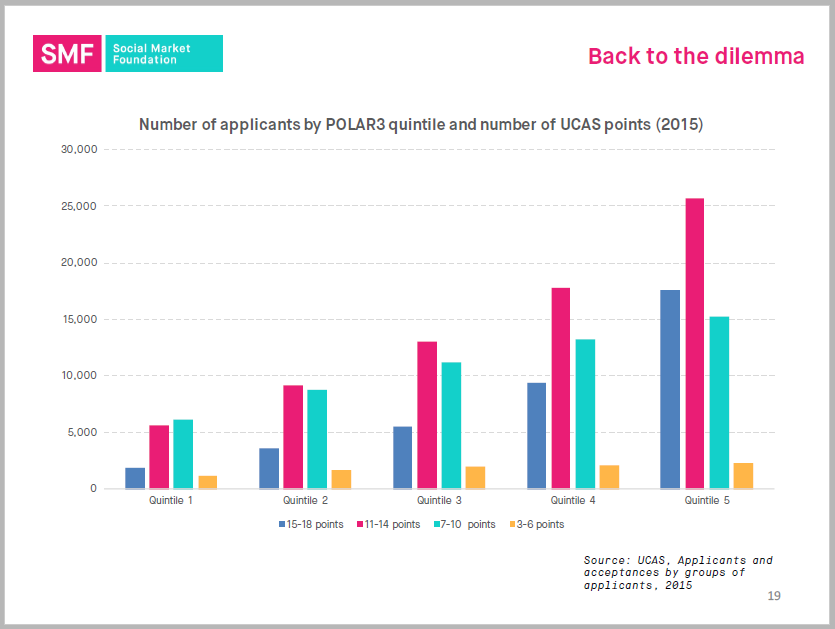

The response of selective universities invariably involves locating the problem further down the food chain by arguing the “real” barrier to access is the attainment gap: the difference in the grades with which young people from different socio-economic backgrounds leave school or college. This position is starkly reinforced by UCAS data reported in the SMF report: in 2015, the total number of young people from society’s most disadvantaged quintile holding entry qualifications that placed them in the top attainment bracket was 1,880; however, the total number of young people from the least disadvantaged backgrounds was 17,560. As the graph below shows, the ratio of high-attaining applicants to low-attaining applicants increases exponentially with socio-economic advantage.

One option suggested by the SMF is that “institutions themselves get much more involved in raising prior attainment.” Clearly, there are important ways in which universities could and should work more closely with lower-attaining state schools and colleges. We can ‘inspire’; we can do more to smooth school-to-university transitions; we can ensure that pupils apply to appropriate course and that our admissions processes treat them justly. Research continues to indicate that young people from low-participation backgrounds conceptualise higher-prestige universities as beyond their reach and worry about not fitting in. Selection practices may also disfavour them.

However, it’s another matter entirely to suggest that university staff have the expertise needed to close attainment differentials. The SMF suggests we offer tuition, provide summer courses and “directly take on responsibility for running schools”. However, the pedagogies favoured in higher education – those that develop critical thinking, independent scholarship and research-driven enquiry – are a far cry from the teach-to-the-test model to which schools are increasingly forced to submit.

If the problem is that the highest prestige universities are not pulling their weight in terms of progress with WP, an alternative approach would be for them to become more sensitive to the educational background in which applicants’ grades were achieved and more explicit about how this information is used in admissions processes. Contextual data is not a new idea, but the sector lacks a consistent, transparent policy on how, when and why it is applied. We even have the absurd situation of league tables using entry tariffs as an indicator of institutional quality, thereby incentivising the more elite end of the sector to continue fishing in familiar waters.

Some colleagues express concern that students admitted on the basis of contextual data might not have the skills needed to cope with higher education. But let’s not forget that state school applicants outperform their independent school peers at university on a like-for-like basis. It’s not so much social engineering as rational investment in talent that hasn’t yet had the opportunity to manifest as attainment.

The SMF doesn’t mention admissions. Instead, it turns to market-based solutions, speculating that some new providers may provide a boost to WP. However, as Andrew McGettigan and others remind us, newly-created private colleges have so far been associated more with empty classrooms and suspect business practices than with driving forward the nation’s social mobility agenda.

The job of improving attainment levels among society’s least advantaged groups is deeply specialised, and one that may be better left to trained, time-served professionals than to well-meaning university staff. However, the sector could seek to address social mobility in other ways. Our rankings could reward diversity and inclusivity, not penalise the use of contextual data. Our admissions processes could become more transparent and less gameable. Our teaching could compensate for previous educational shortcomings by offering targeted, sustained support. And we could fixate a little less on prior attainment and the league tables that peddle it.

Making A Statement

Last week, the Sutton Trust published a Research Brief that I co-authored with the HE Access Network. The theme is a familiar one for me: the UCAS personal statement. I’ve blogged about it here and here, written a previous Sutton Trust report, and published findings in an academic journal and a book about global HE admissions practices.

Last week, the Sutton Trust published a Research Brief that I co-authored with the HE Access Network. The theme is a familiar one for me: the UCAS personal statement. I’ve blogged about it here and here, written a previous Sutton Trust report, and published findings in an academic journal and a book about global HE admissions practices.

This study was a really interesting addition to the evidence because it was the first to compare how teachers at state schools and admission tutors at high-prestige universities read statements. The results were alarming: what teachers think make a good personal statement is a far cry from what universities are looking for.

This study was a really interesting addition to the evidence because it was the first to compare how teachers at state schools and admission tutors at high-prestige universities read statements. The results were alarming: what teachers think make a good personal statement is a far cry from what universities are looking for.

The resear ch attracted plenty of press attention, including an excellent opinion piece by Catherine Bennett for the Observer. Other print coverage included reports in The Sun, The Times, The Daily Telegraph and the Times Education Supplement. My interview on the BBC Radio Four’s Today programme is available here (listen from 52’45”) until February 26th 2016.

ch attracted plenty of press attention, including an excellent opinion piece by Catherine Bennett for the Observer. Other print coverage included reports in The Sun, The Times, The Daily Telegraph and the Times Education Supplement. My interview on the BBC Radio Four’s Today programme is available here (listen from 52’45”) until February 26th 2016.

While I think personal statements offer a useful lens through which to view distributions of social capital and explore teenagers’ self-conceptualisations, I’m hoping this will be the last time I write about them. A review of their use in the application process – ideally as part of a wider review of the HE admissions in the UK – is long overdue.

Revisiting Debates about the UCAS Personal Statement

This post was first published on Oct 14th 2013 by “Manchester Policy Blogs“.

With the first UCAS deadline of the academic year looming, thousands of University hopefuls are putting the finishing touches to their personal statements. But growing evidence points towards the current process favouring some applicants more than others – and it may be time for a radical overhaul, according to Dr Steve Jones.

“The UCAS personal statement is academically irrelevant and biased against poorer students,” ran the headline of one Telegraph blog last month.

According to its author, paying a private company to write your statement now costs between £100 and £200, and the whole thing is little more than “an exercise in spin”. Meanwhile, The Times report that tutors “often ignore students’ personal statements,” describing the indicator as “worthless”.

Perhaps more significantly, last week saw the publication of a Pearson Think Tank report called “(Un)Informed Choices“. The executive summary was surprisingly frank in its recommendation: “the use of personal statements should be ended.”

The debate has interested me since I was commissioned by the Sutton Trust last year to collect new evidence about the personal statement.

My findings were stark. Basic writing errors (like misspelling and apostrophe misuse) were three times more common among applicants from state schools and sixth form colleges as those from independent schools. There were also big differences when it came to work experience: independent school applicants had lots more, and it tended to be high prestige.

All of the statements I looked at were written by students with the same A-level results, so I wondered whether the textual differences offered a partial explanation for the unfair outcomes reported in UK admissions processes more broadly.

For example, research at Durham University has shown that state school applicants are only 60% as likely to be made an offer by Russell Group universities as independent school applicants with the same grades in “facilitating” subjects.

So why hasn’t the personal statement been binned by UCAS already? In my experience, there are five main lines of defence:

1. “Admissions Tutors aren’t taken in by slick expensive personal statements”

This was the response of Cambridge University’s Prof. Mary Beard to my research, and I think it’s a very reasonable point. Any experienced reader of statements will have well-honed “crap detection” skills. Who’s to say our admissions tutors aren’t seeing right through the fancy work placements and LAMDA successes? The problem is, as a sector, we’re neither consistent nor transparent in how personal statements are read. Sometimes they’re given close, critical attention; sometimes not. Either way, we keep schtum about the criteria we use and the weight we attach to them.

2. “There’s never an excuse for spelling mistakes, is there?”

This point was made to me twice by a BBC TV newscaster. The answer is no, there’s never an excuse. However, if you have lots of people to proofread your statement and you’re repeatedly told it’s something you’ve got to get right, chances are you’ll take a bit more care. The sixth form college applicant who made twelve basic language errors in his statement wasn’t stupid – his attainment record proves that – he just didn’t understand how much those mistakes could count against him.

3. “We like to be holistic in the way we select our students”

It’s never easy to argue with the word ‘holistic‘, but there’s no advantage to using lots of indicators unless every one is bringing fairness to the selection process. Perhaps a small amount of appropriately contextualized attainment evidence is actually more equitable than a wide range of hazy non-academic indicators?

4. “We use the personal statement as a starting point for interview questions”

The Oxbridge colleges sometimes use this argument, but it isn’t a very strong one because most UK university applicants aren’t interviewed for any of the degree programmes to which they apply. And, for those that are, surely it’s not beyond interview panels to formulate their own questions? Besides, the most elite universities are often the sniffiest about statements: we don’t want “second-rate historians who happen to play the flute,” says Oxford’s head of admissions; “no tutor believes [the personal statement] to be the sole work of the applicant any more,” says his former counterpart at Cambridge.

5. “Actually, we know personal statements aren’t a reliable, and we don’t bother reading them”

This point is made regularly, but with half a million statements written every year, maybe it’s time someone mentioned it to the young people who stress and sweat over writing them?

There’s room for compromise, of course. In 2004, the Schwartz Report suggested redesigning the UCAS application form to include prompts that elicit more directly relevant information in a more concise fashion. Those applicants with the social and cultural capital to secure the best work experience and highest prestige extra-curricular experience would then have less opportunity to cash in on their good fortune.

But for the last word on the subject, here’s a member of admissions staff (quoted anonymously in the Pearson report) on just how much difference school type can make to the personal statement:

“I’ve spoken to heads of private schools about the question of how much help they give students in writing statements. They say ‘well, they’re paying £7,000 a term, of course we give them a lot of help, that’s what they’re paying for’. And yet you see statements from what [are] potentially good students from schools which have not got a lot of experience of sending their students to HE, and they’re not very good because no-one knows what to do, how to do it.”