HEPI Policy Note 48, by Tom Fryer and Steven Jones, first published here on June 15th 2023.

Category Archives: Admissions

UCAS reforms to the personal statement: One step forward, more to go?

Originally published as HEPI Weekend Reading; written by Tom Fryer, Steve Westlake and Steven Jones

On 12 January, UCAS released Future of Undergraduate Admissions, a report that contained details of five upcoming reforms.

In the report, UCAS proposes to reform the free-text personal statement into a series of questions. This is welcome. As we noted in our recent HEPI Debate Paper on UCAS personal statements, an essay without a question is always going to breed uncertainty.

So the change does represent progress towards a fairer admissions system. However, the number of steps we take towards this fairer system will depend on how the questions are designed.

The UCAS report makes an initial proposal of six questions across the following topics:

- Motivation for Course – Why do you want to study these courses?

- Preparedness for Course – How has your learning so far helped you to be ready to succeed on these courses?

- Preparation through other experiences – What else have you done to help you prepare, and why are these experiences useful?

- Extenuating circumstances – Is there anything that the universities and colleges need to know about, to help them put your achievements and experiences so far into context?

- Preparedness for study – What have you done to prepare yourself for student life?

- Preferred Learning Styles – Which learning and assessment styles best suit you – how do your courses choices match that?

Our first point concerns inequality. To create admissions processes that address inequalities we should use questions that place explicit limits on the number of examples that can be used. If we leave questions open-ended, this risks creating a structure that allows some applicants to gain an advantage over their peers, a key problem with the original format. Also, where possible, questions should stress the acceptability of drawing upon activities, such as caring or part-time work, that may not be deemed ‘high-prestige’. This could minimise the impact of inequalities in access to these ‘high-prestige’ activities. The relatively small number of courses that require formal work experience could gain this information through an optional question.

Secondly, admissions processes should prioritise applicants’ interests and avoid imposing an unnecessary burden. The current proposals contain several questions that appear similar, which does appear to impose an unnecessary workload on applicants and their advisers. We recommend combining the second (course preparedness), third (preparedness through other experiences) and fifth (study preparedness) questions into one, in order to protect applicants’ interests.

Thirdly, other commentators have drawn attention to the association of ‘learning styles’ in question 6 with the widely debunked model that classifies people into four different learning modes: visual; aural; read/write; and kinesthetic. This does not seem to have been UCAS’s intention. Instead through informal conversations we understand the question intended to focus on applicants’ preferences for independent study versus contact time, or frequent short assessments versus substantive end-of-year approaches. Regardless, should applicants’ attitudes to learning and assessment influence admissions decisions? There could be a range of reasons why an applicant has chosen a certain provider, including geographical location for those with caring responsibilities, and many of these will trump concerns about learning styles. We recommend removing this question.

Fourthly, while the report gives evidence that many applicants see the personal statement as an opportunity to advocate for themselves, this alone does not justify the creation of a large number of questions (or indeed, nor does it justify the status quo). Unfortunately, a lack of transparency prevents applicants from understanding how their statement will be read (if it is read at all), and many will be unaware of the research on inequalities in this area. These caveats are important when considering how applicants’ views should feed into discussions about creating an admissions system that protects all applicants.

Our final point relates to validity. Admissions processes should use valid measures of applicants’ ability to complete their chosen courses. Although there is limited research in this area, we think there are opportunities to improve the proposed questions.

To take one example, the first question asks ‘Why do you want to study these courses?’. We contend that an abstract question is unlikely to be the most valid way to assess applicants’ motivations. This question is likely to prompt similarly abstract or cliched answers, including in the form ‘Ever since a child…’. As an alternative, in our HEPI paper, we proposed the following:

Please describe one topic that is related to your course. Please discuss what you have learnt about this topic, through exploring this outside of the classroom. This could include books, articles, blogs, seminars, lectures, documentaries, or any other format.

This question measures both whether an applicant demonstrates a basic level of motivation and whether they understand what is covered on the course. By asking for a concrete example of a topic they have explored, we believe this question is likely to be a more valid way to assess whether applicants meet a basic level of motivation and preparedness, and it is less likely to result in overly abstract or clichéd responses that reveal little about applicants.

UCAS’s proposed reforms to personal statements recognise that fair admissions require greater transparency, a more supportive structure, and the prevention of some applicants being placed at a disadvantage. Moving to a series of questions represents one step forward. However, to achieve these goals, the questions must be designed to address inequality and remove unnecessary burdens in a transparent and valid manner.

There is currently no published research on how personal statements are used in admissions decisions. That’s why we are launching a survey to gather some initial data, which you can access here.

We are particularly seeking input from people involved with the day-to-day work of undergraduate admissions. We would appreciate it if you could share this with any of your colleagues. We plan to use this data to feed into the public conversation about UCAS’s reforms.

UCAS personal statements create inequality and should be replaced by short-response questions

Last week saw the publication of HEPI Debate Paper 31 on Reforming the UCAS Personal Statement.

I’ve been banging on about the UCAS personal statement for over a decade, pointing out that it disadvantages under-represented groups in multiple ways. Initially, there was some pushback (mostly anecdotal), but now there isn’t really much counter-argument at all. Almost everyone in the sector acknowledges that the personal statement is problematic at the very least.

Following the report’s publication, I was asked by a Times Higher journalist why nothing had changed. Being more direct than usual, I said: “Fee-paying schools and colleges have long known that the UCAS personal statement, in its current form, is a chance for their pupils to advantage themselves further in the university application game.”

As well as a powerful independent school lobby persistently advocating for the retention of personal statements, I’d also lay some blame on the elite end of the HE sector. Senior admissions tutors at Russell Group universities often reassure me that nobody actually bothers reading the statements anyway, as though that makes it all okay. Meanwhile, stress levels among students and staff in under-resourced state schools get higher, and the statement continues to provide just enough rope for some applicants to hang themselves.

The HEPI report is an attempt to reach a compromise position. By suggesting that UCAS personal statements should be replaced by short-response questions (rather than scrapped completely), we are trying to meet the sector half way.

I say ‘we‘ but this idea belongs squarely to Tom Fryer, a PhD student of mine. Tom is the report’s main author, and I’m indebted to him for providing new data that supports the case for reform. This data emerges from Write on Point, an organisation that Tom founded to provide young people from under-represented backgrounds with support for writing their statement. Tom is just the kind of thoughtful, self-motivated postgraduate researcher that all supervisors dream of, and I’m very grateful to him for picking up this important issue – and bringing important new evidence to the debate – just as I was beginning to flag!

Will change now happen? Clare Marchant, the chief executive of UCAS, told the Times Higher that she has been working on options for reforming the personal statement since May 2021. Apparently, this has involved consulting with 1,200 students, 170 teachers and advisers, and 100+ universities, and a report outlining proposals for the next admissions cycle will be published in the coming months. But I’m still not holding my breath…

Covid-19 is our best chance to change universities for good

This piece was first published in The Guardian newspaper (31.03.20)

March is normally one of the busiest months in the academic calendar. Lecture theatres bulge, coffee queues lengthen and library shelves empty. The interactions are multilingual and non-stop.

This year, silence. Buildings are in lockdown and staff barred from their offices. Those students who remain are mostly unable to go home.

But learning goes on, displaced, not discontinued. In many respects, Covid-19 is drawing out the best from staff, their commitment to students’ education and wellbeing shining through the uncertainty. Seminars zoom on to students’ smartphones, live from lecturers’ homes. WhatsApp groups, set up very recently to coordinate picketing strategy, become forums in which colleagues can support and advise one another. Behind the scenes – and under-acknowledged – armies of administrative staff and IT workers make all of this possible.

Already, old ways of working seem distant and inexplicable. Were there really so many face-to-face meetings? What did all that bureaucracy achieve? Why did universities submit to so many external metrics? Were we improved by this “accountability” regime? Or did we just get better at playing the market’s games?

For logistical reasons, planned audits of teaching and research such as the National Student Survey and the Research Excellence Framework are on hold or in jeopardy. Could it be the time to consider whether their benefits are proportionate to their costs?

We were told that student consumers could make informed decisions only if able to access maximum information. But the ones I’m now Skyping care little about “value for money” or expected graduate incomes. They are just glad that their learning still matters, and that university staff care about them.

If universities emerge from Covid-19 with trust won back from government – and, crucially, are willing to pass on that trust to frontline staff – post-pandemic higher education could look very different.

Opportunities are everywhere. With no school-based exams this year, university admissions could finally take place in ways that allow fairer access. The move to online teaching could accelerate the decolonisation of curriculums. The shift away from on-campus research could open doors for more collaborative scholarship. Unfettered by physical location, and the compulsion to erect ever-shinier buildings, universities suddenly find themselves free to reimagine their place in society.

Opportunities are everywhere. With no school-based exams this year, university admissions could finally take place in ways that allow fairer access. The move to online teaching could accelerate the decolonisation of curriculums. The shift away from on-campus research could open doors for more collaborative scholarship. Unfettered by physical location, and the compulsion to erect ever-shinier buildings, universities suddenly find themselves free to reimagine their place in society.

Maybe we can collaborate to form a knowledge base that allows future crises to be handled in more informed ways, so that fewer lives become disrupted or endangered? Academic research offers a highly potent antidote to the slew of misinformation and speculation that can jam social media. A single updateable point of truth, based on the most rigorous scholarship available, might help win back public confidence and redeem the tarnished reputation of experts and expertise.

Covid-19 research is being published at a faster pace than sluggish peer review processes customarily allow. And there’s an audible softening of tone from the Office for Students – a regulator previously wedded to competition at all costs, now promising to adapt.

But as lecturers imaginatively pivot to remote teaching, trust issues linger. What will happen to electronically “captured” content when the crisis is over?

A TedX model of teaching could prove attractive to those seeking efficiency savings during the inevitable post-Covid financial squeeze, and predatory “ed-tech” companies are already seeking ways to cash in. But students don’t want passive and distant models of learning. They want technology that brings them closer to specialists in the subject they love. Now is the time to make sure that those staff are valued fully by their employers. Casualisation must dog the sector no more.

For decades, universities have been distracted from their core functions by a regulatory framework and management culture that demanded they vie with one another endlessly for research and teaching income, and for league table recognition. With campuses standing empty, those “wins” seem hollow.

For decades, universities have been distracted from their core functions by a regulatory framework and management culture that demanded they vie with one another endlessly for research and teaching income, and for league table recognition. With campuses standing empty, those “wins” seem hollow.

Staff have already demonstrated their adaptability, intuitively and collegially doing what is right for their students. Now Covid-19 offers a chance for the sector to redefine its relationship with the public, and for university managers to reset their relationship with staff.

Is PQA scepticism damaging the sector’s reputation?

This piece was first published on WonkHE (27.08.19)

Only in the UK does PQA have a name. Post-Qualification Admissions, the practice by which universities make offers to students once their results are known, has been debated every summer since it was first mooted in the Dearing and Schwartz reports of 1997 and 2004 respectively.

The reason that other nations don’t have an equivalent term for PQA is because it’s something they’ve always done. The abbreviation would be as redundant as PPC (post-pregnancy childbirth) or PND (post-night day).

But the UK system is historically wedded to guesswork, making offers to students based on how well their teachers reckon they might do in their exams. We know that such forecasts tend to be imprecise. Research by Gill Wyness demonstrates that nearly one in four disadvantaged students who go on to achieve AAB or better at A-level have their final grades under-predicted. Only 16% of students have every one of their grades prophesied accurately. What’s more, our crystal balls are becoming more, not less, prone to malfunction over time.

Increasingly, there’s political backing for PQA. Shadow Education Secretary Angela Rayner recently reiterated that a Labour government would scrap predicted grades, adding that “our education system must work for students and be driven by fairness, not market forces”. Newspaper editorials point to the UK’s “outdated” model. Danny Dorling, like many senior academics, is a long-time supporter of reform.

Local admissions staff are on board too, with seven out of 10 respondents to a recent survey saying they back PQA. And David Olusoga gets to the heart of why the current admissions process feels unjust to those without the requisite social and cultural capital, likening it to a first encounter with estate agents: “one of those moments in life when the realities of class and privilege are brought out into the open and thrust into the faces of the disadvantaged”.

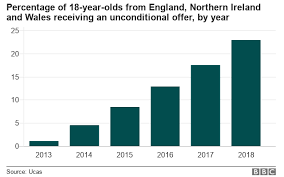

What’s more, PQA would mean an end to the rise in unconditional offers, a practice which possibly breaks consumer law and for which the sector is rightly attacked from all sides. Teachers are aghast that their efforts to secure the very best grades for their students can be so casually undermined one game-playing, supposedly market-savvy university.

In the face of such widespread support for PQA, one might expect the HE sector to embrace the opportunity. At the very least, one might expect acknowledgement that the current system – mostly untouched since the early 1960s – is out of line with what’s now regarded as fair and transparent.

But this is not how sceptics frame PQA. Take the response of UCAS to Angela Raynor’s statement, which argued that:

“If introduced wholesale within the current timetables, [PQA] would be likely to significantly disadvantage underrepresented and disabled students, unless secondary and/or university calendars changed”.

It may be technically correct to say that if PQA were imposed on the sector without any adjustments at all then those (typically middle class) students with in-the-know personal contacts to draw on in mid-summer would be further advantaged. But of course timetables would change. And of course schools and universities would adapt to a new system.

The claim that underrepresented and disabled students would be “significantly” disadvantaged is both premature and speculative, muddying moral waters. Any negatives would need to be carefully and systematically weighed against the many positives of PQA, a system that could potentially open the door for the kind of ambitious, joined-up progress in widening participation that’s long overdue.

Few of the advantages offered by PQA are acknowledged in the UCAS statement, which drifts unhelpfully into paternalistic and market-based language (“our admissions service protects students, enabling them to exercise their consumer rights”), before ending with boasts about high student satisfaction. As Jo Grady notes, it’s a “lazy defence of the status quo”. But it’s also a self-defeating position if it allows the sector to be framed by outsiders as bureaucratic and change-resistant.

Timing is not the only problem with the UK’s admission process. Indeed, as Debbie McVitty points out, arguments about PQA threaten to suck the oxygen from wider conversations about support for under-represented groups. It’s essential that forthcoming reviews look at other problems with the application process.

For example, each UCAS applicant currently requires a reference from their school, something that can take up many hours of valuable staff time. But do generically glowing exaltations really help universities to select the most suitable applicants?

Similarly, my own research for the Sutton Trust has shown that the personal statement disproportionately benefits applicants from better off backgrounds, and that state school teachers struggle to give appropriate guidance to their students because they don’t what universities are looking for in an application. It’s also time we took seriously Vikki Boliver’s finding that ethnic minority applicants to selective universities are less likely to receive offers than comparably qualified white applicants.

No doubt the shift to PQA will create many new challenges, as Chris Husbands and others warn. But the narrow logistical problems aren’t insurmountable. Remember that every other nation’s admissions agency copes perfectly well with a post-qualification system.

What’s vital is that the UK sector doesn’t unwittingly give the impression it’s complacent about equity, and tone deaf to legitimate criticism of its practices. With senior politicians now openly seeking to “rebalance” resources away from higher education, the risk is that excess caution about PQA – justified or not – gives ammunition to those who think the sector has lost touch with what society wants from it.

2019 National Teachers and Advisers Conference – slides

Good to meet so many committed and clued-up school staff at this event last week. Unconditional offers clearly remain a big concern for colleagues in the pre-18 sector, and questions were asked about why universities remains complicit in ‘pressure selling‘ something that it is to the detriment of young people, and may hit disadvantaged youngsters hardest.

The slides from my presentation are here:

2019-05 (final pdf) – Steven Jones – UoM – National Teachers and Advisers Conference.

It’s not easy to raise prior attainment, but universities could better contextualise applicants’ grades

Note: this piece was originally published here on LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog.

The government has challenged the Higher Education sector to double the proportion of pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds and to raise by 20 per cent the number of undergraduates from Black and Minority Ethnic backgrounds. However, last month’s report by the Social Market Foundation (SMF) casts doubt on the achievability of either goal.

Among the observations offered by the SMF is that the spread of disadvantaged students across UK universities is very patchy. While some institutions’ Widening Participation (WP) intake is pushing 30 per cent, proportions elsewhere barely top 2 per cent. No surprise there, perhaps. But what may come as more of a shock are differences in the rate of improvement. As the SMF graph below shows, progress since 2009 among Top 10 institutions (according to rankings in the Times Higher) is less than half that made by institutions ranked 11-20 and by those outside the Top 20. In other words, the rate at which the UK’s highest prestige universities are growing their WP intake is more sluggish than everywhere else.

Does that matter? Well, as the Social Mobility and Child Poverty commission has noted, the top professions tend to be dominated by alumni of the highest ranking universities. And according to the Sutton Trust, graduates from such universities enjoy the more substantial earnings premium. The risk is that the sector’s uneven distribution of WP students allows social hierarchies to be reproduced and causes social mobility to stall.

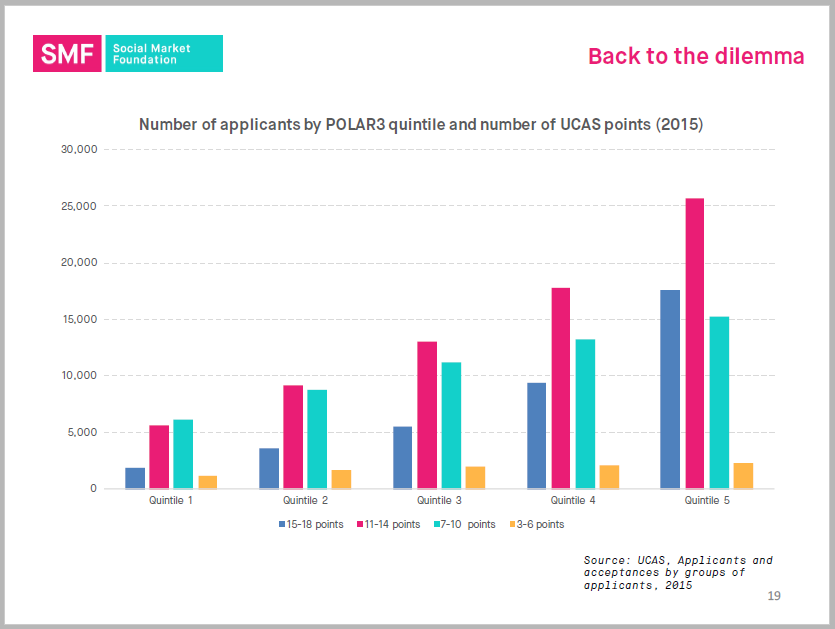

The response of selective universities invariably involves locating the problem further down the food chain by arguing the “real” barrier to access is the attainment gap: the difference in the grades with which young people from different socio-economic backgrounds leave school or college. This position is starkly reinforced by UCAS data reported in the SMF report: in 2015, the total number of young people from society’s most disadvantaged quintile holding entry qualifications that placed them in the top attainment bracket was 1,880; however, the total number of young people from the least disadvantaged backgrounds was 17,560. As the graph below shows, the ratio of high-attaining applicants to low-attaining applicants increases exponentially with socio-economic advantage.

One option suggested by the SMF is that “institutions themselves get much more involved in raising prior attainment.” Clearly, there are important ways in which universities could and should work more closely with lower-attaining state schools and colleges. We can ‘inspire’; we can do more to smooth school-to-university transitions; we can ensure that pupils apply to appropriate course and that our admissions processes treat them justly. Research continues to indicate that young people from low-participation backgrounds conceptualise higher-prestige universities as beyond their reach and worry about not fitting in. Selection practices may also disfavour them.

However, it’s another matter entirely to suggest that university staff have the expertise needed to close attainment differentials. The SMF suggests we offer tuition, provide summer courses and “directly take on responsibility for running schools”. However, the pedagogies favoured in higher education – those that develop critical thinking, independent scholarship and research-driven enquiry – are a far cry from the teach-to-the-test model to which schools are increasingly forced to submit.

If the problem is that the highest prestige universities are not pulling their weight in terms of progress with WP, an alternative approach would be for them to become more sensitive to the educational background in which applicants’ grades were achieved and more explicit about how this information is used in admissions processes. Contextual data is not a new idea, but the sector lacks a consistent, transparent policy on how, when and why it is applied. We even have the absurd situation of league tables using entry tariffs as an indicator of institutional quality, thereby incentivising the more elite end of the sector to continue fishing in familiar waters.

Some colleagues express concern that students admitted on the basis of contextual data might not have the skills needed to cope with higher education. But let’s not forget that state school applicants outperform their independent school peers at university on a like-for-like basis. It’s not so much social engineering as rational investment in talent that hasn’t yet had the opportunity to manifest as attainment.

The SMF doesn’t mention admissions. Instead, it turns to market-based solutions, speculating that some new providers may provide a boost to WP. However, as Andrew McGettigan and others remind us, newly-created private colleges have so far been associated more with empty classrooms and suspect business practices than with driving forward the nation’s social mobility agenda.

The job of improving attainment levels among society’s least advantaged groups is deeply specialised, and one that may be better left to trained, time-served professionals than to well-meaning university staff. However, the sector could seek to address social mobility in other ways. Our rankings could reward diversity and inclusivity, not penalise the use of contextual data. Our admissions processes could become more transparent and less gameable. Our teaching could compensate for previous educational shortcomings by offering targeted, sustained support. And we could fixate a little less on prior attainment and the league tables that peddle it.

Making A Statement

Last week, the Sutton Trust published a Research Brief that I co-authored with the HE Access Network. The theme is a familiar one for me: the UCAS personal statement. I’ve blogged about it here and here, written a previous Sutton Trust report, and published findings in an academic journal and a book about global HE admissions practices.

Last week, the Sutton Trust published a Research Brief that I co-authored with the HE Access Network. The theme is a familiar one for me: the UCAS personal statement. I’ve blogged about it here and here, written a previous Sutton Trust report, and published findings in an academic journal and a book about global HE admissions practices.

This study was a really interesting addition to the evidence because it was the first to compare how teachers at state schools and admission tutors at high-prestige universities read statements. The results were alarming: what teachers think make a good personal statement is a far cry from what universities are looking for.

This study was a really interesting addition to the evidence because it was the first to compare how teachers at state schools and admission tutors at high-prestige universities read statements. The results were alarming: what teachers think make a good personal statement is a far cry from what universities are looking for.

The resear ch attracted plenty of press attention, including an excellent opinion piece by Catherine Bennett for the Observer. Other print coverage included reports in The Sun, The Times, The Daily Telegraph and the Times Education Supplement. My interview on the BBC Radio Four’s Today programme is available here (listen from 52’45”) until February 26th 2016.

ch attracted plenty of press attention, including an excellent opinion piece by Catherine Bennett for the Observer. Other print coverage included reports in The Sun, The Times, The Daily Telegraph and the Times Education Supplement. My interview on the BBC Radio Four’s Today programme is available here (listen from 52’45”) until February 26th 2016.

While I think personal statements offer a useful lens through which to view distributions of social capital and explore teenagers’ self-conceptualisations, I’m hoping this will be the last time I write about them. A review of their use in the application process – ideally as part of a wider review of the HE admissions in the UK – is long overdue.

What’s in a name?

Note: this piece was originally published as Anonymising UCAS forms is only a first step towards fair and discrimination-free university admissions on LSE’s Democratic Audit blog.

When pledging to make university applications “name-blind”, the Prime Minister yesterday cited research showing that top universities make offers to 55% of white applicants but only to 23% of black applicants. From 2017, universities will follow major employers that “recruit solely on merit” by offering anonymity to their applicants.

When pledging to make university applications “name-blind”, the Prime Minister yesterday cited research showing that top universities make offers to 55% of white applicants but only to 23% of black applicants. From 2017, universities will follow major employers that “recruit solely on merit” by offering anonymity to their applicants.

In many respects, this is a sensible move. Universities can hardly claim immunity from ‘unconscious bias’, and admissions processes could be seen to exemplify the “quieter and more subtle discrimination” that the Prime Minister wishes to address. However, those of us who have looked closely at the issue would argue that concealing candidates’ names does not go far enough.

In 2012, I authored a report for the Sutton Trust showing that the quality of UCAS personal statements could be predicted by applicants’ school type. For example, those from Sixth Form Colleges and Comprehensive Schools made several times more basic spelling and grammar errors than those from Grammar Schools and Independent Schools. Ethnicity was also a major factor, with British-Bangladeshi applicant making 2.29 errors per 1,000 words of statement, compared to white applicants’ 1.42 errors. All of the statements I examined were written young people who went on to achieve identical grades at A-level. The differences in their statements were not down to ability; they were down the amount of help and guidance available.

There are other ways in which our university application systems may reproduce existing forms of privilege. Candidates from the fee-paying sector are much more likely to mention the name of their school in their personal statement, even though this information is captured elsewhere in their application, perhaps as a means to accentuate their perceived fit for leading universities. Social capital is demonstrated through prestigious work placements, internships and job shadowing experiences; cultural capital through overseas trips and LAMDA examinations. Evidence suggests that interviews are no less discriminatory, with some candidates drilled extensively in how to perform under pressure while others remain intimidated by an unfamiliar, hostile environment.

There are other ways in which our university application systems may reproduce existing forms of privilege. Candidates from the fee-paying sector are much more likely to mention the name of their school in their personal statement, even though this information is captured elsewhere in their application, perhaps as a means to accentuate their perceived fit for leading universities. Social capital is demonstrated through prestigious work placements, internships and job shadowing experiences; cultural capital through overseas trips and LAMDA examinations. Evidence suggests that interviews are no less discriminatory, with some candidates drilled extensively in how to perform under pressure while others remain intimidated by an unfamiliar, hostile environment.

So how should selective universities select when almost every indicator is potentially problematic and we cannot be trusted with even a candidate’s name? An extreme solution, favoured by some European countries, is to allocate places on over-subscribed courses based on a lottery for those who meet a minimum academic threshold. Other nations, notably the USA, ask for statements but offer greater reassurance to students from under-represented backgrounds that their application will be read in its appropriate context and the odd spelling mistake will not count against them. Few nations rely on the personal statement as much as the UK. However, with Independent Schools increasingly competing with one another on entry rates to leading universities, and with new markets emerging around the tutoring and coaching of applicants, the pressure to maintain the status quo is considerable.

The Prime Minister is right to say that the UK Higher Education sector needs to take a close look at why young people from some backgrounds can be disadvantaged in the application process. We also need to understand better why ethnicity predicts the likelihood of graduating with a higher degree award. But to stop at anonymised applications would be to pretend that the root of the problem is a handful of prejudiced admissions tutors. The candidate’s name is not the only issue. Indeed, this information may allow more sympathetic admissions tutors to make appropriate allowances. If the goal is to bring greater fairness to the process, we also need to think about more systemic issues, such as why offers are made on predicted rather than actual grades, how candidates’ attainment can be suitably contextualised, and why personal statements are given more prominence than any evidence suggests they are worth.

The Prime Minister is right to say that the UK Higher Education sector needs to take a close look at why young people from some backgrounds can be disadvantaged in the application process. We also need to understand better why ethnicity predicts the likelihood of graduating with a higher degree award. But to stop at anonymised applications would be to pretend that the root of the problem is a handful of prejudiced admissions tutors. The candidate’s name is not the only issue. Indeed, this information may allow more sympathetic admissions tutors to make appropriate allowances. If the goal is to bring greater fairness to the process, we also need to think about more systemic issues, such as why offers are made on predicted rather than actual grades, how candidates’ attainment can be suitably contextualised, and why personal statements are given more prominence than any evidence suggests they are worth.

Have UCAS really revealed “the language tricks which will help you land that place at a top university”?

UCAS, the agency responsible for admissions to Higher Education in the UK, last week issued an analysis of the personal statements of 300,000 university applicants. They’d totted up the number of ‘passion-related’ words (such as “love” and “explore”) and ‘career-oriented words’ (“salary”, “employable”, “job”, etc.) to see how frequencies differed according to the subjects for which candidates were applying.

Journalists seemed unsure what to make of the press release. “In all subjects, applicants used a mixture of career and passion-related words to set out their suitability,” reported The Telegraph. “It’s not a huge surprise,” admitted another report, “that artsy students have cornered the passion market”. One reporter noted aimlessly that “despite the prominence of economics and economists over the last few years, students wanting to major in economics are among those least likely to mention either a ‘career’-related word”.

But none of the reports questioned whether such words are actually valued by admissions tutors. This gave the unfortunate impression that all applicants needed to do was use the right vocabulary and their place at university would be secure. The Mirror even promised to reveal “how to strike the balance between ‘passion and purpose’ to NAIL your written application”.

UCAS, of course, can hardly be blamed for such misreporting. But it’s no secret that admissions tutors are rarely seduced by the language of love:

Dr Hilary Hinds, an admissions tutor from the English department at Lancaster University, finds clichés such as “passionate about literature” and “I’ve loved books for as long as I can remember” dull and predictable. “Demonstrate it rather than claim it,” she says. (The Guardian, 10.07.15)

My own research into the language of personal statements confirms that Dr Hinds isn’t alone. Words like “passion” and “love” are used more by applicants from state schools than those from independent schools, and they correlate negatively with the likelihood of acceptance by higher-prestige universities.

The press interest generated by the UCAS study was vacuous (at best) and specious (at worst). A far better use of the large, rich, not-publicly-available database would have been to identify patterns of use according to factors known to affect candidates’ chances of success, such as ethnicity and socio-economic status.