HEPI Policy Note 48, by Tom Fryer and Steven Jones, first published here on June 15th 2023.

Tag Archives: UCAS

UCAS reforms to the personal statement: One step forward, more to go?

Originally published as HEPI Weekend Reading; written by Tom Fryer, Steve Westlake and Steven Jones

On 12 January, UCAS released Future of Undergraduate Admissions, a report that contained details of five upcoming reforms.

In the report, UCAS proposes to reform the free-text personal statement into a series of questions. This is welcome. As we noted in our recent HEPI Debate Paper on UCAS personal statements, an essay without a question is always going to breed uncertainty.

So the change does represent progress towards a fairer admissions system. However, the number of steps we take towards this fairer system will depend on how the questions are designed.

The UCAS report makes an initial proposal of six questions across the following topics:

- Motivation for Course – Why do you want to study these courses?

- Preparedness for Course – How has your learning so far helped you to be ready to succeed on these courses?

- Preparation through other experiences – What else have you done to help you prepare, and why are these experiences useful?

- Extenuating circumstances – Is there anything that the universities and colleges need to know about, to help them put your achievements and experiences so far into context?

- Preparedness for study – What have you done to prepare yourself for student life?

- Preferred Learning Styles – Which learning and assessment styles best suit you – how do your courses choices match that?

Our first point concerns inequality. To create admissions processes that address inequalities we should use questions that place explicit limits on the number of examples that can be used. If we leave questions open-ended, this risks creating a structure that allows some applicants to gain an advantage over their peers, a key problem with the original format. Also, where possible, questions should stress the acceptability of drawing upon activities, such as caring or part-time work, that may not be deemed ‘high-prestige’. This could minimise the impact of inequalities in access to these ‘high-prestige’ activities. The relatively small number of courses that require formal work experience could gain this information through an optional question.

Secondly, admissions processes should prioritise applicants’ interests and avoid imposing an unnecessary burden. The current proposals contain several questions that appear similar, which does appear to impose an unnecessary workload on applicants and their advisers. We recommend combining the second (course preparedness), third (preparedness through other experiences) and fifth (study preparedness) questions into one, in order to protect applicants’ interests.

Thirdly, other commentators have drawn attention to the association of ‘learning styles’ in question 6 with the widely debunked model that classifies people into four different learning modes: visual; aural; read/write; and kinesthetic. This does not seem to have been UCAS’s intention. Instead through informal conversations we understand the question intended to focus on applicants’ preferences for independent study versus contact time, or frequent short assessments versus substantive end-of-year approaches. Regardless, should applicants’ attitudes to learning and assessment influence admissions decisions? There could be a range of reasons why an applicant has chosen a certain provider, including geographical location for those with caring responsibilities, and many of these will trump concerns about learning styles. We recommend removing this question.

Fourthly, while the report gives evidence that many applicants see the personal statement as an opportunity to advocate for themselves, this alone does not justify the creation of a large number of questions (or indeed, nor does it justify the status quo). Unfortunately, a lack of transparency prevents applicants from understanding how their statement will be read (if it is read at all), and many will be unaware of the research on inequalities in this area. These caveats are important when considering how applicants’ views should feed into discussions about creating an admissions system that protects all applicants.

Our final point relates to validity. Admissions processes should use valid measures of applicants’ ability to complete their chosen courses. Although there is limited research in this area, we think there are opportunities to improve the proposed questions.

To take one example, the first question asks ‘Why do you want to study these courses?’. We contend that an abstract question is unlikely to be the most valid way to assess applicants’ motivations. This question is likely to prompt similarly abstract or cliched answers, including in the form ‘Ever since a child…’. As an alternative, in our HEPI paper, we proposed the following:

Please describe one topic that is related to your course. Please discuss what you have learnt about this topic, through exploring this outside of the classroom. This could include books, articles, blogs, seminars, lectures, documentaries, or any other format.

This question measures both whether an applicant demonstrates a basic level of motivation and whether they understand what is covered on the course. By asking for a concrete example of a topic they have explored, we believe this question is likely to be a more valid way to assess whether applicants meet a basic level of motivation and preparedness, and it is less likely to result in overly abstract or clichéd responses that reveal little about applicants.

UCAS’s proposed reforms to personal statements recognise that fair admissions require greater transparency, a more supportive structure, and the prevention of some applicants being placed at a disadvantage. Moving to a series of questions represents one step forward. However, to achieve these goals, the questions must be designed to address inequality and remove unnecessary burdens in a transparent and valid manner.

There is currently no published research on how personal statements are used in admissions decisions. That’s why we are launching a survey to gather some initial data, which you can access here.

We are particularly seeking input from people involved with the day-to-day work of undergraduate admissions. We would appreciate it if you could share this with any of your colleagues. We plan to use this data to feed into the public conversation about UCAS’s reforms.

UCAS personal statements create inequality and should be replaced by short-response questions

Last week saw the publication of HEPI Debate Paper 31 on Reforming the UCAS Personal Statement.

I’ve been banging on about the UCAS personal statement for over a decade, pointing out that it disadvantages under-represented groups in multiple ways. Initially, there was some pushback (mostly anecdotal), but now there isn’t really much counter-argument at all. Almost everyone in the sector acknowledges that the personal statement is problematic at the very least.

Following the report’s publication, I was asked by a Times Higher journalist why nothing had changed. Being more direct than usual, I said: “Fee-paying schools and colleges have long known that the UCAS personal statement, in its current form, is a chance for their pupils to advantage themselves further in the university application game.”

As well as a powerful independent school lobby persistently advocating for the retention of personal statements, I’d also lay some blame on the elite end of the HE sector. Senior admissions tutors at Russell Group universities often reassure me that nobody actually bothers reading the statements anyway, as though that makes it all okay. Meanwhile, stress levels among students and staff in under-resourced state schools get higher, and the statement continues to provide just enough rope for some applicants to hang themselves.

The HEPI report is an attempt to reach a compromise position. By suggesting that UCAS personal statements should be replaced by short-response questions (rather than scrapped completely), we are trying to meet the sector half way.

I say ‘we‘ but this idea belongs squarely to Tom Fryer, a PhD student of mine. Tom is the report’s main author, and I’m indebted to him for providing new data that supports the case for reform. This data emerges from Write on Point, an organisation that Tom founded to provide young people from under-represented backgrounds with support for writing their statement. Tom is just the kind of thoughtful, self-motivated postgraduate researcher that all supervisors dream of, and I’m very grateful to him for picking up this important issue – and bringing important new evidence to the debate – just as I was beginning to flag!

Will change now happen? Clare Marchant, the chief executive of UCAS, told the Times Higher that she has been working on options for reforming the personal statement since May 2021. Apparently, this has involved consulting with 1,200 students, 170 teachers and advisers, and 100+ universities, and a report outlining proposals for the next admissions cycle will be published in the coming months. But I’m still not holding my breath…

Is PQA scepticism damaging the sector’s reputation?

This piece was first published on WonkHE (27.08.19)

Only in the UK does PQA have a name. Post-Qualification Admissions, the practice by which universities make offers to students once their results are known, has been debated every summer since it was first mooted in the Dearing and Schwartz reports of 1997 and 2004 respectively.

The reason that other nations don’t have an equivalent term for PQA is because it’s something they’ve always done. The abbreviation would be as redundant as PPC (post-pregnancy childbirth) or PND (post-night day).

But the UK system is historically wedded to guesswork, making offers to students based on how well their teachers reckon they might do in their exams. We know that such forecasts tend to be imprecise. Research by Gill Wyness demonstrates that nearly one in four disadvantaged students who go on to achieve AAB or better at A-level have their final grades under-predicted. Only 16% of students have every one of their grades prophesied accurately. What’s more, our crystal balls are becoming more, not less, prone to malfunction over time.

Increasingly, there’s political backing for PQA. Shadow Education Secretary Angela Rayner recently reiterated that a Labour government would scrap predicted grades, adding that “our education system must work for students and be driven by fairness, not market forces”. Newspaper editorials point to the UK’s “outdated” model. Danny Dorling, like many senior academics, is a long-time supporter of reform.

Local admissions staff are on board too, with seven out of 10 respondents to a recent survey saying they back PQA. And David Olusoga gets to the heart of why the current admissions process feels unjust to those without the requisite social and cultural capital, likening it to a first encounter with estate agents: “one of those moments in life when the realities of class and privilege are brought out into the open and thrust into the faces of the disadvantaged”.

What’s more, PQA would mean an end to the rise in unconditional offers, a practice which possibly breaks consumer law and for which the sector is rightly attacked from all sides. Teachers are aghast that their efforts to secure the very best grades for their students can be so casually undermined one game-playing, supposedly market-savvy university.

In the face of such widespread support for PQA, one might expect the HE sector to embrace the opportunity. At the very least, one might expect acknowledgement that the current system – mostly untouched since the early 1960s – is out of line with what’s now regarded as fair and transparent.

But this is not how sceptics frame PQA. Take the response of UCAS to Angela Raynor’s statement, which argued that:

“If introduced wholesale within the current timetables, [PQA] would be likely to significantly disadvantage underrepresented and disabled students, unless secondary and/or university calendars changed”.

It may be technically correct to say that if PQA were imposed on the sector without any adjustments at all then those (typically middle class) students with in-the-know personal contacts to draw on in mid-summer would be further advantaged. But of course timetables would change. And of course schools and universities would adapt to a new system.

The claim that underrepresented and disabled students would be “significantly” disadvantaged is both premature and speculative, muddying moral waters. Any negatives would need to be carefully and systematically weighed against the many positives of PQA, a system that could potentially open the door for the kind of ambitious, joined-up progress in widening participation that’s long overdue.

Few of the advantages offered by PQA are acknowledged in the UCAS statement, which drifts unhelpfully into paternalistic and market-based language (“our admissions service protects students, enabling them to exercise their consumer rights”), before ending with boasts about high student satisfaction. As Jo Grady notes, it’s a “lazy defence of the status quo”. But it’s also a self-defeating position if it allows the sector to be framed by outsiders as bureaucratic and change-resistant.

Timing is not the only problem with the UK’s admission process. Indeed, as Debbie McVitty points out, arguments about PQA threaten to suck the oxygen from wider conversations about support for under-represented groups. It’s essential that forthcoming reviews look at other problems with the application process.

For example, each UCAS applicant currently requires a reference from their school, something that can take up many hours of valuable staff time. But do generically glowing exaltations really help universities to select the most suitable applicants?

Similarly, my own research for the Sutton Trust has shown that the personal statement disproportionately benefits applicants from better off backgrounds, and that state school teachers struggle to give appropriate guidance to their students because they don’t what universities are looking for in an application. It’s also time we took seriously Vikki Boliver’s finding that ethnic minority applicants to selective universities are less likely to receive offers than comparably qualified white applicants.

No doubt the shift to PQA will create many new challenges, as Chris Husbands and others warn. But the narrow logistical problems aren’t insurmountable. Remember that every other nation’s admissions agency copes perfectly well with a post-qualification system.

What’s vital is that the UK sector doesn’t unwittingly give the impression it’s complacent about equity, and tone deaf to legitimate criticism of its practices. With senior politicians now openly seeking to “rebalance” resources away from higher education, the risk is that excess caution about PQA – justified or not – gives ammunition to those who think the sector has lost touch with what society wants from it.

Narrowing participation: calculating the likely impact of two-year degrees isn’t simple maths

This piece was originally published on the LSE’s Politics and Policy blog (December 20th 2017)

For some, the numbers are straightforward. You take the 78 weeks ostensibly needed for an undergraduate degree, and you squash them into two years instead of three. You raise tuition fees for each of those two years, but make sure that the overall cost of the degree remains lower than for the three-year version. Then you sit back and watch as your accelerated degrees lead to accelerated job market entry and accelerated student loan repayments.

Perhaps that’s part of the thinking behind the consultation recently launched by the government. Some newspapers went out of their way to frame the proposal as a breakthrough for young people. The Express picked up on the idea that two-year degrees will “save students £25,000,” a figure arrived at by opportunistically adding one year’s projected graduate income to the actual saving. A Telegraph piece made unsupported claims about knowledge accumulation being stunted during the long summer months, and two-year degrees enabling stronger friendships to be forged. That students currently spend half of their degree “on holidays,” the report claimed, was “astonishing”.

What’s astonishing is that such myths persist. The students that I teach, and who’ve participated in research projects with which I’ve been involved, rarely talk of holidays. What they do talk about are the part-time jobs they need to pay down urgent debts, and often to top up maintenance loans. And the unpaid work experience they need to get a graduate job. And the performance anxiety that’s inevitable when there’s so much at stake.

Non-teaching time is often used for independent learning, with dissertations planned, re-sits revised for, and course reading absorbed in advance. Universities facilitate, and increasingly expect, academic engagement the whole year round. It’s hardly a ‘high-drink, low-work’ culture, and it’s very different from the summers that policy-makers and commentators may fondly recollect, where some ventured overseas to ‘find themselves’ while others stayed home to sign on.

Like most lecturers, I receive (and respond to) hundreds of e-mails from students during ‘holiday’ periods. But academics are routinely positioned as part of the problem, perhaps softened up in public discourse by mischievous tweets about their “sacrosanct” three-month summer break.

As usual, ‘diversity’ is framed as a key driver for change (because how can anyone be anti-diversity?), but when it comes to accelerated degrees the heavy lifting would most likely be done not by the elite providers but by those institutions already over-achieving in terms of widening participation. It’s greater choice, perhaps, but it’s not the kind of diversity that the sector requires: cultural and academic mixing, across institutions, regardless of socioeconomic and ethnic background.

The Office of Fair Access welcomed the proposals as a response to the alarming drop in mature students since the 2012 fees hike. But mature students, always more likely to be juggling family and workplace commitments, have historically been drawn to slower, part-time, and flexible routes. It’s unclear how many would embrace an accelerated option.

Is the financial incentive meaningful? Perhaps, but given how few graduates are now projected to pay off their student loan in full, it’s questionable whether a modest cut in the total bill would make much difference. Concerns have been raised that the two-year degree is a backdoor route to higher fees.

The 2017 end-of-cycle report from UCAS show the participation gap – the difference in likelihood of attending university between those in the most and least disadvantaged quintiles – extending for a third consecutive year. It’s now as wide as it has been at any point in the last decade. Could accelerated degrees divide society further, as those with the financial means and the cultural inclination to study at a leisurely pace become further detached from their less fortunate peers? Will employers value a two-year degree if those from the higher socioeconomic quintiles quietly ignore it?

That only 0.2% of students are currently enrolled on an accelerated degree programme does suggest more could be done to accommodate the needs of young people who make an informed decision to opt for a shorter programme. But in the current climate, it’s too easy to dismiss the ‘one-size-fits-all’ model of undergraduate teaching as another example of universities’ self-interest. The impression given by supporters of the two-year route is that students are left twiddling their thumbs every summer, but this understates the immense academic and financial pressure under which they find themselves.

The main objection to accelerated degrees is that some students will continue to enjoy an all-round university experience, as their parents did, while others will be fast-tracked towards premature entry into a precarious graduate labour market. Mathematically, three years of learning could indeed be compressed into two. But what complicates the calculation is that the option to accelerate would be viewed very differently across social classes.

The University Game

I’m looking forward to giving a Sarah Fielden seminar on May 11th at the University of Manchester. All welcome. Further details here.

What’s in a name?

Note: this piece was originally published as Anonymising UCAS forms is only a first step towards fair and discrimination-free university admissions on LSE’s Democratic Audit blog.

When pledging to make university applications “name-blind”, the Prime Minister yesterday cited research showing that top universities make offers to 55% of white applicants but only to 23% of black applicants. From 2017, universities will follow major employers that “recruit solely on merit” by offering anonymity to their applicants.

When pledging to make university applications “name-blind”, the Prime Minister yesterday cited research showing that top universities make offers to 55% of white applicants but only to 23% of black applicants. From 2017, universities will follow major employers that “recruit solely on merit” by offering anonymity to their applicants.

In many respects, this is a sensible move. Universities can hardly claim immunity from ‘unconscious bias’, and admissions processes could be seen to exemplify the “quieter and more subtle discrimination” that the Prime Minister wishes to address. However, those of us who have looked closely at the issue would argue that concealing candidates’ names does not go far enough.

In 2012, I authored a report for the Sutton Trust showing that the quality of UCAS personal statements could be predicted by applicants’ school type. For example, those from Sixth Form Colleges and Comprehensive Schools made several times more basic spelling and grammar errors than those from Grammar Schools and Independent Schools. Ethnicity was also a major factor, with British-Bangladeshi applicant making 2.29 errors per 1,000 words of statement, compared to white applicants’ 1.42 errors. All of the statements I examined were written young people who went on to achieve identical grades at A-level. The differences in their statements were not down to ability; they were down the amount of help and guidance available.

There are other ways in which our university application systems may reproduce existing forms of privilege. Candidates from the fee-paying sector are much more likely to mention the name of their school in their personal statement, even though this information is captured elsewhere in their application, perhaps as a means to accentuate their perceived fit for leading universities. Social capital is demonstrated through prestigious work placements, internships and job shadowing experiences; cultural capital through overseas trips and LAMDA examinations. Evidence suggests that interviews are no less discriminatory, with some candidates drilled extensively in how to perform under pressure while others remain intimidated by an unfamiliar, hostile environment.

There are other ways in which our university application systems may reproduce existing forms of privilege. Candidates from the fee-paying sector are much more likely to mention the name of their school in their personal statement, even though this information is captured elsewhere in their application, perhaps as a means to accentuate their perceived fit for leading universities. Social capital is demonstrated through prestigious work placements, internships and job shadowing experiences; cultural capital through overseas trips and LAMDA examinations. Evidence suggests that interviews are no less discriminatory, with some candidates drilled extensively in how to perform under pressure while others remain intimidated by an unfamiliar, hostile environment.

So how should selective universities select when almost every indicator is potentially problematic and we cannot be trusted with even a candidate’s name? An extreme solution, favoured by some European countries, is to allocate places on over-subscribed courses based on a lottery for those who meet a minimum academic threshold. Other nations, notably the USA, ask for statements but offer greater reassurance to students from under-represented backgrounds that their application will be read in its appropriate context and the odd spelling mistake will not count against them. Few nations rely on the personal statement as much as the UK. However, with Independent Schools increasingly competing with one another on entry rates to leading universities, and with new markets emerging around the tutoring and coaching of applicants, the pressure to maintain the status quo is considerable.

The Prime Minister is right to say that the UK Higher Education sector needs to take a close look at why young people from some backgrounds can be disadvantaged in the application process. We also need to understand better why ethnicity predicts the likelihood of graduating with a higher degree award. But to stop at anonymised applications would be to pretend that the root of the problem is a handful of prejudiced admissions tutors. The candidate’s name is not the only issue. Indeed, this information may allow more sympathetic admissions tutors to make appropriate allowances. If the goal is to bring greater fairness to the process, we also need to think about more systemic issues, such as why offers are made on predicted rather than actual grades, how candidates’ attainment can be suitably contextualised, and why personal statements are given more prominence than any evidence suggests they are worth.

The Prime Minister is right to say that the UK Higher Education sector needs to take a close look at why young people from some backgrounds can be disadvantaged in the application process. We also need to understand better why ethnicity predicts the likelihood of graduating with a higher degree award. But to stop at anonymised applications would be to pretend that the root of the problem is a handful of prejudiced admissions tutors. The candidate’s name is not the only issue. Indeed, this information may allow more sympathetic admissions tutors to make appropriate allowances. If the goal is to bring greater fairness to the process, we also need to think about more systemic issues, such as why offers are made on predicted rather than actual grades, how candidates’ attainment can be suitably contextualised, and why personal statements are given more prominence than any evidence suggests they are worth.

Have UCAS really revealed “the language tricks which will help you land that place at a top university”?

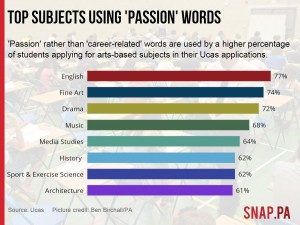

UCAS, the agency responsible for admissions to Higher Education in the UK, last week issued an analysis of the personal statements of 300,000 university applicants. They’d totted up the number of ‘passion-related’ words (such as “love” and “explore”) and ‘career-oriented words’ (“salary”, “employable”, “job”, etc.) to see how frequencies differed according to the subjects for which candidates were applying.

Journalists seemed unsure what to make of the press release. “In all subjects, applicants used a mixture of career and passion-related words to set out their suitability,” reported The Telegraph. “It’s not a huge surprise,” admitted another report, “that artsy students have cornered the passion market”. One reporter noted aimlessly that “despite the prominence of economics and economists over the last few years, students wanting to major in economics are among those least likely to mention either a ‘career’-related word”.

But none of the reports questioned whether such words are actually valued by admissions tutors. This gave the unfortunate impression that all applicants needed to do was use the right vocabulary and their place at university would be secure. The Mirror even promised to reveal “how to strike the balance between ‘passion and purpose’ to NAIL your written application”.

UCAS, of course, can hardly be blamed for such misreporting. But it’s no secret that admissions tutors are rarely seduced by the language of love:

Dr Hilary Hinds, an admissions tutor from the English department at Lancaster University, finds clichés such as “passionate about literature” and “I’ve loved books for as long as I can remember” dull and predictable. “Demonstrate it rather than claim it,” she says. (The Guardian, 10.07.15)

My own research into the language of personal statements confirms that Dr Hinds isn’t alone. Words like “passion” and “love” are used more by applicants from state schools than those from independent schools, and they correlate negatively with the likelihood of acceptance by higher-prestige universities.

The press interest generated by the UCAS study was vacuous (at best) and specious (at worst). A far better use of the large, rich, not-publicly-available database would have been to identify patterns of use according to factors known to affect candidates’ chances of success, such as ethnicity and socio-economic status.

The Role of Ethnicity in Admissions to Russell Group Universities

(Note: I published this piece first on the British Educational Research Association’s Respecting Children & Young People blog on 17.03.15…)

Here’s an excerpt from a UCAS personal statement written recently by an applicant to a Russell Group university:

“There are various times where I have been a team member such as in hockey, this is where we have to understand our team member’s strengths and weaknesses to evaluate best positions, it makes us understand that one’s ability may be skilful but can always be tackled by two. We had to quickly judge aspects; we also understood how goals and motivation can go through team members, as high motivation can motivate another.”

Within the excerpt, some details have been altered to protect the applicant’s identity. However, the writing style is unchanged and captures that of the whole statement.

A natural first response is that the applicant doesn’t belong at a high-prestige institution: the text is poorly punctuated, with muddled content, and reads as though it were thrown together at the last moment. Thank goodness for UCAS personal statements, one might conclude, for allowing universities additional evidence on which to make important selection decisions.

Except things aren’t quite so straightforward.

First, note that this applicant went on to receive A-level grades that were sufficient to gain entry to the courses for which she applied. This suggests that her personal statement difficulties were not caused by a lack of academic ability so much as confusion about what was required. Second, studies like this one, this one and this one, question whether personal statements are really of much value in predicting students’ subsequent performance at university anyway. Third, the applicant was educated in the state sector, and evidence suggests that she may therefore have had limited access to the kind of high quality information, advice and guidance available to many of her competitors. And fourth, the applicant is of British-Bangladeshi heritage, a group which fares poorly in admissions to high-prestige universities compared with White applicants of similar academic attainment.

In 2012, I undertook research for the Sutton Trust looking at how university applicants from different backgrounds set about the task of writing their personal statement. My primary focus was on school type, and I discovered that applicants from Sixth Form Colleges and Comprehensive Schools were much more likely to make basic language errors (spelling mistakes, apostrophe misuse, etc.) than those from Grammar schools and Independent Schools. Workplace experience could also be predicted by school type, with some applicants able to list up to a dozen placements at flash companies while others struggled to make a Saturday job sound relevant to their chosen course of study.

I’ve since returned to the data to find out whether personal statements also differ according to the ethnicity of the applicant. On average, I discovered, British-Bangladeshi applicants make 2.29 clear linguistic errors per 1,000 words of statement, compared to White applicants’ 1.42 errors. British-Bangladeshi applicants are also low on meaningful work-related activity, averaging 1.57 per statement compared to 2.32 for White applicants (where ‘meaningful’ means undertaken for genuine vocational experience rather than for cash – all such activities were blind coded by two text analysts). The total sample size is 327, and all of the statements were submitted by students who would go on to achieve identical A-level grades.

What prompted me to carry out these new counts was the graph below, based on UCAS data analysis by Durham University’s Vikki Boliver. This analysis showed that applicants’ chances of getting an offer from a Russell Group university differed markedly according to their ethnicity. British-Bangladeshi students have a 42.6% likelihood; White British students a 52.0% likelihood.

Source: Boliver in Alexander and Arday (2015), via Economics of HE

As Parel and Boliver note, ethnicity actually trumps school type as a predictor of admission to leading UK universities. Figures obtained from Oxford University by the Guardian in 2013 under the Freedom of Information Act indicated that “43% of White students who went on to receive three or more A* grades at A-level got offers, compared with 22.1% of minority students”.

Such differentials can be explained in many ways. Even though Boliver’s data controls for ‘facilitating’ subjects (those the Russell Group claim are preferred by universities), it could be that Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) applicants take inappropriate combinations for the degree courses to which they apply. It has also been implied that BAME applicants tend toward oversubscribed subjects, such as medicine or law. However, as Boliver continues to point out, the kind of individual-level data needed to develop a clear picture of why differentials arise is increasingly being restricted because, supposedly, it “presents a high risk of individuals’ personal details being disclosed.”

Does the application process itself discriminate against some applicants? I’ve written before about how the UCAS personal statement is, in many respects, a flawed indicator, and I’ve also responded to specific arguments made in its defence. Other researchers have noted similar problems with university interviews (see Burke and McManus on would-be Art & Design students who make the mistake of citing hip-hop as an influence, or Zimdars on a tendency for admissions tutors at Oxford University to recruit in their own image).

Does the application process itself discriminate against some applicants? I’ve written before about how the UCAS personal statement is, in many respects, a flawed indicator, and I’ve also responded to specific arguments made in its defence. Other researchers have noted similar problems with university interviews (see Burke and McManus on would-be Art & Design students who make the mistake of citing hip-hop as an influence, or Zimdars on a tendency for admissions tutors at Oxford University to recruit in their own image).

Such studies raise awkward but crucial questions about what exactly non-academic indicators are supposed to indicate. Is the personal statement simply an “opportunity to tell us about yourself”, as UCAS benignly describes it, or is the real goal to flaunt one’s cultural and social capital, signalling what Bourdieu characterises as the “dispositions to be, and above all to become, ‘one of us’”?

The Observer’s Barbara Ellen notes that certain kinds of applicant are much more likely to “speak uni” and be able to “decode the foreign language of the admissions process.” And Pilkington reminds us that BAME applicants are “entitled to know that they will not be subject to potentially indirect − or indeed direct − discriminatory practices in an institution’s admissions processes.”

However, the problem may well go beyond the level of institution. A key structural barrier seems to be an admissions process that assumes all applicants are equally equipped to understand (and have sufficient support to meet) its veiled requirements. The personal statement purports to help university admission tutors make informed choices based on holistic evidence, but may actually reproduce White and other forms of privilege at the point of application.

The UCAS personal statement: “just enough rope for a hanging”?

(Note: I published this piece first in Research Fortnight on A-level results day, 2014…)

For many students, A-level results day is the culmination of a lengthy and complex university application process involving open days, UCAS forms, grade predictions, school references and admissions interviews. For some, the game will have started even earlier, with awards, experiences and sporting endeavours accumulated throughout adolescence on the promise that “this’ll look good on your personal statement.”

But Britain’s approach to undergraduate admissions is the exception, not the norm. Elsewhere in the world, systems tend to be more sensitive to uneven distributions of social capital, extra-curricular opportunities and guidance from friends, family and school. At a recent international conference, delegates from Northern European countries began to chuckle when I explained that applicants to British universities are given 4,000 characters to write freely about themselves. They felt sure such an indicator would reveal less about the applicant than their social and cultural background. Similar suspicions were raised in the 2004 Schwartz Report, which warned that “some staff and parents advise to the extent that the personal statement cannot be seen as the applicant’s own work.”

The alternative for many nations is appropriately contextualised attainment data. Rather than turn to non-academic criteria to choose between eligible applicants, universities in both Holland and Greece have experimented with lotteries to distribute places on oversubscribed programmes. Meet your course’s entry requirements and your name goes into a hat with every other applicant who reaches that threshold. No gaming the system with interview coaching, LAMDA examinations or extravagant work placements.

Even in the largely decentralised US admissions system, applicants must respond to ‘prompts’, including those below, that are designed to make the process fairer. Such prompts, rather than encourage applicants to cash in on past opportunities, call for focused, candid and reflective responses. College websites in the US reassure applicants that statements will be read “in their true context” (Princeton), and justify the use of non-academic indicators in terms of a “long history of encouraging diversity” (Brown).

My interest in the higher education admissions was sparked by Vikki Boliver’s 2012 finding that “applicants to Russell Group universities from state schools are less than two-thirds as likely to receive offers as privately educated applicants,” a differential that wasn’t attributable to ‘facilitating’ subjects. Last month, a study of 50,000 students by the University of Bristol confirmed similar concerns in relation to ethnic minority applicants. For example, for every 100 candidates of Pakistani ethnicity, seven fewer offers were made than for 100 equivalent white British candidates, a pattern that “could not be fully explained by differences in academic attainment or patterns of application.”

Last year, I published Sutton Trust funded research demonstrating that equal-attainment students submitted very different personal statements. Basic linguistic errors (such as spelling errors and apostrophe misuse) were almost three times more common in statements submitted by applicants attending sixth form colleges than by those attending independent schools. For some candidates, work experience meant school-facilitated day trips and paid Saturday jobs; for others, it involved shadowing public figures and undertaking high-prestige placements. My findings resonated with a 2010 survey by the Education and Employers Taskforce showing that 42% of young people from independent schools felt their work experience helped them get into university, as opposed to only 25% of those from comprehensive schools.

Of course, it’s possible that admission tutors see through advantages of school type to the candidate beneath. “Does the Sutton Trust really think I’m taken in by slick expensive personal statements?” tweeted Prof Mary Beard when my report first appeared. But last year The Times reported that statements were now regarded as “worthless” by many tutors, and the recent Pearson Think Tank report, (Un)Informed Choices, concluded that “the use of personal statements should be ended.” Unless all students’ applications are judged by staff with the experience and skill to separate privilege from potential, it’s difficult to excuse the continued use of an indicator that, according to a 1996 paper by Karen Surman Paley, affords hopefuls “just enough rope for a hanging.”

Whether this year’s A-level results bring good news or bad for individual students, questions remain about whether the half a million or so personal statements written every year represent an efficient use of time, energy and resource, either for schools and colleges or for the higher education sector. A growing body of evidence suggests that non-academic indicators, rather than bringing equality to the selection process, further advantage those applicants already favoured by school type and socio-economic background.