In 2012, following a near-trebling of student fees in England, recruitment fell by 9%.

However, 2013’s headline is that normal service has now been resumed. Indeed, entry levels are close to a record high.

This is good news for all. That HE brings both individual and societal gains is well established. Rumours persist that participation may even offer the odd cultural benefit, though ‘public good‘ remains a phrase conspicuously absent from most wider discussions of HE.

History will also record 2013 as the year in which the mature student began heading towards extinction. Application rates for those aged 21 or over have fallen 14% since the fees hike, and there’s little real hope of recovery. (Note that the graph below covers only 18-year-old applicants.) Prospects look similarly bleak for would-be UK postgraduates.

On a more positive note, the 2013 National Student Survey found undergraduates to be happier with their lot than ever before. A blunt instrument though the NSS is, it would be churlish to argue that the ‘student experience’ hasn’t improved since its launch in 2005. 85% of graduating students are satisfied with their degree programme.

With universities now all REF‘d out, the pendulum is likely to swing back towards teaching. For England’s 1.5 million £9k-a-year paying undergrads, this can only be good news.

Private universities continued to be welcomed into the English HE market, though the New College of the Humanities fell short of its very modest recruitment targets once again. Three-quarters of its £18k-a-year paying students attended an independent school.

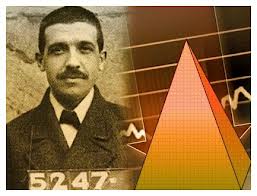

Such was demand elsewhere, however, the government was left with a black hole in its budget. With plans to sell off the student loan books being likened to a Ponzi scheme, some wonder why we seem intent on following the US down the path of bubbling, unsustainable student debt at a time when Germany are abandoning their fees experiment altogether.

Sadly, 2013 saw the demise of the 1994 Group. Meanwhile, the University Alliance’s end-of-year message raised eyebrows by commending the government for courageously taking the “economic and moral high ground” (my italics). It also raised questions about what exactly HE mission groups and consortia are for.

Politically, Willetts and Cable continue to pull the strings, while Graduate Tax advocate Liam Byrne replaced Shabana Mahmood as Labour’s Shadow HE minister.

Universities UK got told off by Polly Toynbee for suggesting it’s okay to segregate female and male students, and Sussex Uni quickly reversed its decision to suspend five students for protesting peacefully.

In terms of WP, the proportion of poorer students applying for university held firm, though ‘top’ universities continue to recruit at much lower levels than other institutions.

According to a Sutton Trust report issued in November, at least one quarter of this “access gap” can’t be attributed to academic achievement, further evidence that there may be more to Russell Group under-representation than A-level performance.

And what to expect from 2014?

Well, English universities will soon be able to take as many students as they like. That’s good news for many, but it could increase the pressure on struggling institutions to maintain market share as their sought-after WP students are lured elsewhere.

Universities free from recruitment anxieties will continue to press for the £9k cap to rise.

Meanwhile, early applications figures for 2014 are down 3% on the same time last year.

Long-term, it may not be the headline £9,000 figure that’s most damaging to the HE sector.

Rather – as I’ve argued elsewhere this year – a bigger problem could be continued uncertainty about the security, fairness and expense of the student loan system itself.